Home | News | Biography | Publications | Research | Gallery | Audio/Visual | Links

The Interviews

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Breaking the circle of silence about Anfal women

- towards building a national archive for Anfal

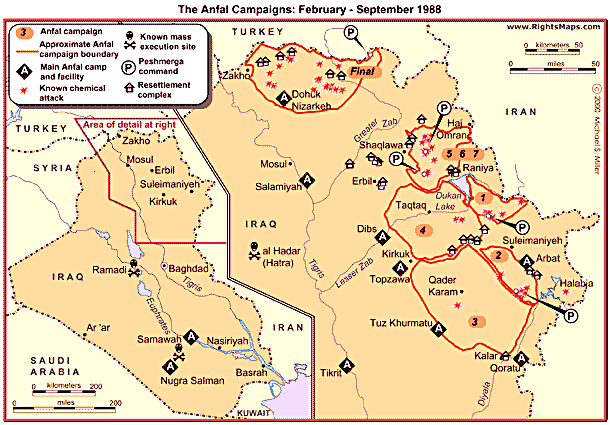

The term ‘Anfal’ which means ‘spoils of war’ is the name of the eighth chapter of the Qura’an which came to the prophet in the wake of his first jihad against the non-believers. The Iraqi government used this word to refer to a series of military operations which targeted Kurdish Muslims in the north of Iraq from February to September 1988. By using this word the government intended to mobilise support from within the country and to legitimise the operations in the Muslim world, portraying the Kurds as non-Muslims. Anfal took place in eight stages, targeting six geographically identified areas (see map below). In this process over 2600 Kurdish villages were destroyed and an estimated number of 100,000 civilians ended up in mass graves. Many more died as a result of bombardment, gas attacks, exodus to Iran and Turkey and life in the camps (Topzawa, Dibis, Nugra Salman, Nizarka, Salamya).

Source: http://www.rightsmaps.com/html/anfalful.html

At the beginning of each Anfal stage chemical attacks were used to kill, terrify and destroy the morale of the people. After the air raids and alongside conventional bombing the ground attacks started. The attacks were designed to steer civilians towards certain collection points near main roads where they were awaited by the army and the jash forces (Kurdish mercenaries who worked for the Iraqi government). The civilians were then taken in coaster busses, trucks and military vehicles (IFA trucks) towards the forts and army camps which acted as assembling and processing centres (Suleimanya Emergency Forces (Tawari), Chemchemal Brigade Headquarters (Liwa), Qoratu Fort, Tuz Khurmatu Youth Centre, Aliawa jash headquarters, Laylan Animal Pen, Taqtaq Military Garrison and Fort, Harmouta Army camp, Qadir Karam Elementary School and Police Station) and then to the temporary holding centres (Topzawa Popular Army Camp (Anfals 1-7) and Qala’t Dohok (Anfal 8)). They were then divided into three main groups: the men and teenage boys, the women and their children, and the elderly. The women were transferred to Dibis prison (in the Soran region, Anfals 1-7) and Salamiya near Mousel (in the Badinan region 8th Anfal). The elderly were taken to Nugra Salman on the border of Saudi Arabia. The men were stripped down to their vests and sharwal (Kurdish baggy trousers). Their hands were tied behind them and they were blindfolded and taken to the mass graves. Most of the men were executed within days of their capture but some are reported to have been alive a few years after Anfal. After the September 1988 General Amnesty large parts of Iraqi Kurdistan remained ‘prohibited for security reasons’ and the surviving inhabitants (mostly women, children and the elderly) were forcibly relocated to housing complexes near the main cities. The survivors were left to fend for themselves without support or compensation. They were not entitled to food coupons and their children were not allowed to go to school because they were not considered Iraqi citizens.

Tuz Khurmatu Youth Centre (looking down from the roof). This is a large one storey building with a courtyard in the middle. This was one of the assembling centres during the 3rd Anfal (the Germian region). The people of Tuz Khurmatu demonstrated against the government when the villagers were being brought to this Youth Centre. The chaos helped some people to escape. A mustashar (jash leader) who is known to have helped many women and children escape was called Jabara Drej (Jabar the Tall). According to many women he had been deceived about the purpose of the Anfal campaign, believing that it was a deportation campaign. Once he realised that the people will be annihilated he quickly switched his loyalty and urged his jash and the general public to help the villagers escape. He was allegedly killed by the Iraqi government in 1991.

One of the halls in Tuz Khurmatu Youth Centre. Women and children were helped to escape from the high windows. Members of the jash forces dangled their Kurdish belts (pishten) to pull out women and children. Tuz Khurmatu Youth Centre is now occupied by dozens of internally displaced families who have built mud brick walls to divide up the large halls. It is also full of abandoned furniture, chicken and children.

Topzawa Popular Army Camp is a large one storey building spreading over two square miles. The camp was surrounded by barbed wire during Anfal. The majority of the people who were captured during Anfals 1-7 were processed through Topzawa. For most of the men this was their last stop before execution. In the large courtyard hills of men’s clothes, their rosaries, knives, mirrors, combs and ID cards were piled up. Women repeatedly talked about the piles of clothes, ID cards and men’s belongings soaking in the rain and mud.

The remains of one of the halls in Topzawa. There were around 30 large halls each 25-30 meters long. The windows were barred and netted but had no glass. It was from these windows that the women watched the blindfolded and handcuffed men who were forced to run around the blocks before they were shoved into the closed military trucks (described as large ambulances or windowless busses) which took them to their death.

Qala’at Dohok at Nizarka (Dohok Castle). This is a gigantic two storey building which became the temporary holding centre during the final Anfal (the 8th). Thousands of people from the Bahdinan region were taken there. As was the custom in Topzawa the men were immediately separated from the rest of the villagers, blindfolded and handcuffed. A number of men were killed by being hacked in the head with concrete blocks on the day of their arrival. The rest were soon taken to the mass graves leaving behind all their personal belongings.

Qala’at Dohok. Like many other buildings of oppression and brutality now the Dohok castle is buzzing with life as displaced and homeless families have made their homes there. In the large courtyard in the middle of the building there are dozens of children playing.

My research about Anfal women

I am grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for a two year scholarship which allowed me to research about the women survivors of Anfal. Here I will present a selection of the data collected between October 2005 and June 2006. In this period I travelled to the remote Kurdish villages and housing complexes where the Anfal survivors live. The dominant Anfal narrative speaks of 182,000 civilians who were shot in the mass graves, the destruction of 4000 Kurdish villages, the extensive use of chemical weapons, the crushed Kurdish liberation movement, and the fact that genocide was carried out against the Kurds. The plight of women during Anfal, how they coped during the campaign and in its aftermath is not part of the dominant narrative. My objective has been to find out about how women experienced the mass violence and its aftermath, in particular the issues of coping with loss, the burden of silence about sexual abuse, and rebuilding life after the atrocities.

I am not arguing that women are not present in the Anfal commemorations. On the contrary, women are regularly interviewed by the media and spoken about by Kurdish politicians. What I am interested in is how women are represented by the media and politicians. A particularly popular image in the media is that of women lamenting their ‘disappeared’ husbands and children by crying and singing a lullaby. The image of women inflicting pain on themselves and lamenting the loss of their loved ones became a typical image of the Anfal women, an image which they are expected to sustain every time they are visited by journalists. These images have been repeatedly used by the Kurdish media to convey the horrors of Anfal. Later they were used by the Kurdish Regional Government during the election campaigns to urge people not to forget what happened to them under a non-Kurdish government and to encourage people to vote for them. Over the years this expectation to talk and cry and portraying women like hopeless victims became a form of abuse by journalists who wanted to make sensational documentaries. Through this research I have also found that for the women survivors Anfal did not end in September 1988. The poverty, deprivation, stigmatisation and lack of support that followed are as much part of the Anfal story as the gas attacks, disappearances and destruction. These experiences, however, and the women’s complaints about the Kurdish authorities are not part of the dominant Anfal narrative.

Here, I don’t intend to reject the facts that make up the Anfal narrative in favour of another version based on women’s experiences. I merely want to question the accepted narrative and to expand it so that it includes women’s experiences. Butalia (1997:93), when talking about women’s silence about abduction and rape during the partition of India, points out that ‘in recovering histories of those who are relegated to the margins, we have little option but to look at sources other than the accepted ones, and in doing so to question, stretch and expand the notion of what we see as history.’ This is because memory is elusive and not without ‘contradictions’ and ‘ambivalences’ (Butalia, 1997:94). Recreating the Anfal narrative based on the facts and the sidelined experiences and memories of women will only enhance our understanding of Anfal.

The interviews presented here were all conducted in Kurdish, recorded on camera and then translated and transcribed by myself. The testimonies are divided into different sections: Camp survivors, Gas Survivors, Those who managed to hide during Anfal, Refugees, and the testimony of activists and politicians. I hope that this data will be useful to researchers and other people who want to find out more about this genocide campaign.